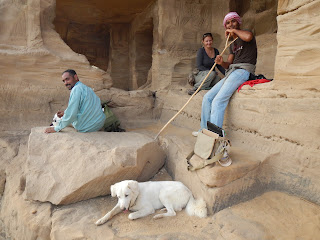

The landscape of Shatt el-Rigal in

the northern part of Gebel el-Silsila, where many hundreds of Middle Kingdom

rock inscriptions have been discovered.

Gebel el-Silsila was an important

quarrying site from earliest times, offering a plentiful supply of good quality

sandstone for pharaoh’s building projects, as well as being a vital strategic

trading point on the boundary between Egypt and Nubia.

A Continuation of Rock Art

As we highlighted in our previous

article (AE113), since earliest times, people coming to Gebel el-Silsila have

left their marks on the rock faces. Moving from prehistory to early history, it

is evident that early dynastic rock art is less common than during previous

periods. With the development of the hieroglyphic and hieratic scripts, there

is instead a clear change from pictographic images to textual rock

inscriptions, which normally consist of names and titles. When rock art is found,

the early dynastic repertoire reproduces many of the previous motifs, including

hunting scenes (men, dogs, and captured animals), designs from the natural

fauna, boats, and so on. New for Gebel el-Silsila in this period is the

appearance of footprints or sandals, and anthropomorphic figures are portrayed

not only as hunters, but are also shown in praising positions, and soon

thereafter as deities.

By the beginning of the Middle

Kingdom (c. 2055 BC), figural rock art had developed into complex scenes, exemplified

in a panel in the southern-most part of the West Bank. The scene depicts a

human figure with raised arms, a dog, and several horned animals – a

traditional hunting scene – but with the addition of several birds identified

by John Wyatt as ostriches, and a crowning circle, most likely representing the

sun. Thus, sun worship has arrived at Gebel el-Silsila.

When Gebel el-Silsila Became Kheny

The ancient Egyptian name of Gebel

el-Silsila was Kheny or Khenu ![]()

which is generally translated as the “Rowing

Place”, but could equally signify the “Mouth of the River”. Its earliest

attestation is a reference from a Fourth Dynasty mastaba at Dahshur belonging

to prince Iynefer, son of Sneferu. Shortly thereafter the earliest hieroglyphic

inscription at Gebel el- Silsila itself appears: a cartouche of Pepy I, located

along the main cenotaph pathway on the West Bank (Rock Inscription Site

GeSW.RIS.8). Surrounding this royal name is a vast number of Middle Kingdom

signatures as well as a couple of Predynastic giraffes, and graffiti from later

visitors to the site. No other Old Kingdom texts have been confirmed thus far.

It is plausible that the site had already become a state-controlled quarry by

this time, considering Pepy’s other quarry expeditions to Nubia. However, the

strategic location of Gebel el-Silsila, with a clear line of sight in all

directions, may also have inspired the army to set up a camp there and use the

site as a for- ward base for military campaigns into Nubia.

The name Kheny occurs again in a Middle Kingdom papyrus, acquired in Thebes at the end of the nineteenth century by Charles Edwin Wilbour. This text later came into the possession of the Brooklyn Museum, and was labelled as Papyrus Brooklyn 35.1446. Written in black ink hieratic, line 21 gives the name of a fugitive of the state called “Hemenusra, son of Khnumhotep” and describes him as a “man of Rokhen(y) of the department of the plough-lands of …”. The topographic name is generally accepted as denoting “Kheny”, marking the border with Nubia, at Egypt’s south- ern-most point.

Another text, Papyrus Berlin 10495, provides us with the topographic name of Kheny in a list of seventeen Middle Kingdom fortresses. Here the site is again considered the boundary between Egypt and Nubia, but now marking the northern-most fortress in Nubia. The two references to Gebel el-Silsila as a boundary between Egypt and Nubia are supported on site as well, epigraphically, geologically and archaeologically. As we will see below, Rock Inscription Sites 11-12 are situated at the edge of the mountainscape on the plateau, and overlook the entire plain to the south, which today is agricultural land stretching all the way down to the Roman Ras Ras Temple (just south of Gebel el-Silsila, north of Kom Ombo).

Thus, the Rock Inscription Sites mark a natural

boundary in the south, which is perhaps why they were marked with several

cartouches of Senusret I, the Twelfth Dynasty king who first extended Egypt’s

southern border. The natural boundary is also marked in the geological

formation of the gorge which, when the Nile’s waters receded after the

inundation, became like a cataract which people and animals could safely cross.

Epigraphically, the team has located a Middle Kingdom inscription giving the

name of an “overseer of the fortress”, which supports the information given in

Papyrus Berlin 10495. Additionally, the team has recently identified a

structure that may have functioned as a fortress, which will be excavated next

season.

Middle Kingdom Activity

There are several focal points for

the ongoing epigraphic and archaeological documentation of Middle Kingdom sig-

natures and activity in the region. The area under investigation begins at the

famous Wadi Shatt el-Rigal in the north and meanders along the Nile and the plateau

to the far south of Gebel el- Silsila (West Bank) where the mountain meets the

agricultural belt. Sections of a wide paved road survive throughout this area,

and several inscriptions have been documented on the horizontal rock surface,

next to the piles of stone created during the preparation work for the building

of the road (clearing of the road surface).

Since Petrie’s studies at the site,

several scholars have documented Middle Kingdom presence in the north,

naturally focusing on the cliff-faces adjacent with the monumental scene of

Mentuhotep II. However, despite the efforts of Caminos and his students in the

1980s, barely any of the texts strewn across the landscape of Gebel el-Silsila

have been published. To rectify this, our team began a larger archaeological

study in 2013, which led to the discovery of hundreds of signatures and shorter

texts that occasionally provide us with information regarding the geographic

origin and profession of individuals and their activity in the region. From

this, we have been able to create a directory of several individuals active on

site during the Eleventh and Twelfth Dynasties. Two areas of Middle Kingdom

activity will be summarised here: ‘Pottery Hill’ (= Rock Inscription Site 9)

and ‘Senusret’s Rocks’ (= Rock Inscription Sites 11-12).

Pottery Hill – GeSW.RIS.9

Several inscriptions are situated

in an area known to the team as Pottery Hill, which is a small mound containing

a cluster of twenty-eight stone huts that were used by the quarry workers for

storage. It is located on the plateau above a quarry harbour on the west bank.

The nickname Pottery Hill derives from the fact that the mound is littered with

pottery: thousands and thousands of sherds that bear witness to a once very

active site. The team’s archaeo-ceramicist Dr. Sarah K. Doherty carried out an

analysis of this pottery and discovered the majority was used for the storage

of food and liquids. As with all archaeological sites, material visible on the

surface belongs to the last phase of activity; at Pottery Hill the pottery

primarily dates to the Roman Period. However, immediately below and to the

north of the texts – and they run from north to south, reading from the right.

The team recently published a selection of these texts, providing us with the names

and professions of several visitors:

“Seal-bearer (or treasurer) of the

God, Ihawka”

“Expedition leader, Sobek-hotep”

“Overseer of the southern quarry,

Thenn”

“Overseer of the southern quarry,

Khonsu-hotep”

“Overseer of the southern quarry,

Ankhemara”

“… of the southern quarry, director

of the crew, Ptah-Seshem”

“Quarry inspector Meru”.

Several of the names already occur

during the Old Kingdom, but other names, such as Meru, are certainly names only

found from the Middle Kingdom, for which a Middle Kingdom date has been

proposed. The team believes these texts belong to a group of high-ranking

officials involved in the quarry expeditions. In addition to the texts, there

are depictions of two boats, one of which is similar to a vessel occasionally

used as a determinative for the place-name of Kheny. The

presence of two boats may emphasise the nature of the expedition or specify the

professions of the men listed. For example, the title is a frequent nautical

title, used by the crew leader, which presumably from Gebel el-Silsila by ship.

Moreover, the word translated here as ‘quarry’ may incorporate a reference to

the nautical element of quarry work, that is a hill, the paved road and its

series of inscriptions indicate there was already activity at Pottery Hill

during the Middle Kingdom.

The texts are arranged neatly together

on a smooth, horizontal rock surface, in an area cleared from pebbles and sand,

adjacent to a large stone pile. They are positioned so as to be read from the

road and Pottery Hill – that is for a person standing to the east of the

quarried harbour or a quay associated with the quarries. Such a harbour is

located immediately below Pottery Hill. There is also a standing figure of the

local hippopotamus-goddess Tausret (although severely eroded) as well as a

footprint/sandal print with a Middle Kingdom signature. The text inside the

footprint is poorly preserved and very faded, but the style of the owl-sign is

identical to those of adjacent Middle Kingdom texts, confirming its Middle

Kingdom date. While feet and sandal graffiti occur frequently during later

dynastic periods, the Gebel el- Silsila graffito is unique in confirming the

existence of footprint carvings as early as the Middle Kingdom.

Senusret’s Rock – GeSW.RIS.11-12

The Rock Inscription Site known to the team as Senusret’s Rock is located in the far south of Gebel el-Silsila, at the edge of the plateau overlooking the agricultural plain. The boulder- like outcrop that makes up the RIS displays a total of forty-two pictorial and textual engravings, ranging from Predynastic petroglyphs to Roman game boards. A vast number, though, are Middle Kingdom texts providing us, again, with the names and (sometimes) professions of the people once active on site. Among the more important texts are three repetitions of the birth and throne names of Senusret I, two of which are oriented towards the east, and the third southwards. The best example is a horizontal cartouche situated on a vertical, south-facing cliff-face of locale GeSW.RIS.12.

“Year 45 (of the reign) of King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Kheper-ka-Ra, Son of Ra, Senusret”

Current Thoughts on Gebel el-Silsila during the Middle Kingdom

Over the millennia, the Nile forced

its way into the sandstone massif to create a deep and narrow gorge, providing

the ancient Egyptians of the Middle Kingdom with a strategic location from

which to oversee, and protect Egypt from, its southern neighbours. The

formation of this nature-given barrier likely gave rise to the site’s ancient

name, Kheny, the ‘Mouth of the River’. Presumably, the site was also a

lucrative quarrying location. The combination of natural barricades in all

directions, and a supply of valuable golden sandstone made Gebel el-Silsila the

ideal site for a fortified military encampment to protect the quarries and

facilitate trade.

As mentioned above, the team has

now found epigraphic evidence of a fortress in an unpublished Middle Kingdom

inscription by the ‘overseer of the fort’. This title confirms the inventory of

Middle Kingdom fortresses listed in Papyrus Berlin 10495. However, with no

excavation or documentary evidence for such a fortress – Sir A.H. Gardiner

himself declared “no fortress is known at Silsilis” – there has been no attempt

to understand the site’s position within the larger landscape until now.

Line of Sight

There is one method that is applied

to all investigations of landscape archaeology at Gebel el-Silsila (and

elsewhere): the ancient use of ‘line of sight’ as a means of connecting various

structures. At Gebel el-Silsila the team used this method early on to record

the relative locations of a string of coexistent Roman stations, outlook posts,

and structures. The results show their arrangement was deliberate and designed

in such a way as to ensure mutual protection and safety, regular communication

and to aid travellers journeying to and from neighbouring towns.

During the Roman Period, it was clear that structures on the East Bank of Gebel el-Silsila had direct line of sight to the location of Ras Ras on the West Bank a few kilometres to the south.

From there, this chain of

visibility zig- zagged back and forth across the Nile to Kom Ombo and further

south. A similar pattern is discernible to the north, where Gebel el-Silsila

connects by sight line to the fortified town of el-Serag (ancient Thumis),

which in turn connects with Edfu, and further to Gebelein, towards Thebes.

Crucially, these alignments allowed a visible interaction between the various

locales, probably by beacons or other noticeable signs, enabling warnings or

support to be sent when needed. A similar system would have been in place

allowing communication between the Middle Kingdom fortresses.

Another important factor to

remember is that large parts of the river would have been impassable during the

inundation, as the current would have been too strong. This is especially true

for Gebel el-Silsila, having a bottleneck- shaped gorge where the floodwaters

would have gushed. Certainly, the flooded landscape would allow enemies a

chance to attack the area unless it was protected from higher ground.

Geological and landscape studies at Gebel el-Silsila have revealed that many of

the wadis (valleys) were flooded, and at times the waters partially encircled

the two mountains (Gebel el-Silsila itself on the East Bank, and partially Ramada

Gibli on the West). During this time, the wadis could be used to circumnavigate

the main river, so that the movement of troops, traders, and all that was

needed to sustain a functioning infrastructure (and to process stone) could

continue unabated. Wadi Shatt el-Rigal is one such example, with hundreds of

Middle Kingdom texts and graffiti (including the famous Mentuhotep II scene), proof that the wadi was a busy corridor.

Our team has only scratched the

surface of Middle Kingdom activity in the region, but with hundreds of texts

documented (some recently published, and more prepared, including the name of

the Major of Kheny!), the documentation of Middle Kingdom quarrying techniques,

road systems, and other infrastructure, and the planned excavations of what

could be a fortress, we hope to be able to paint a more detailed picture of

Middle Kingdom life at Gebel el-Silsila.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our

wonderful Silsila family, and the Permanent Committee of Foreign Missions for

giving the team permission to work at Gebel el-Silsila, and equally the General

Director of Aswan and Nubia, Mr A. Moniem Said. The documentation of MK

epigraphy and archaeology has been made possible by the financial support of

Gerda Henkel Stiftung, Magnus Bergvalls Stiftelse, and Crafoordska Stiftelsen.

Again, we would like to thank Ancient Egypt Magazine for allowing us to share the paper here!

All photo and material published herein are the property and copyrighted the Gebel el-Silsila Project. For permit of reuse for publications, please contact the directors.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)